Atoruru PHC's Rebirth: A Tale of Resilience and Recovery Amid Global Health Challenges

A Community at the Crossroads

Situated amidst the hilly landscape and flourishing farmlands of Sabongida Ora, Owan West LGA, Edo State, the rural community of Atoruru has long been inhabited by industrious farmers, enterprising traders, and families whose lives are interwoven like the roots of the old iroko trees that shade a village square. In its early years, the Atoruru Primary Health Care Centre (PHC) stood as the community's resilient but struggling heartbeat, a place where new life entered the world, yet where many mothers and children faced preventable health challenges. Though dedicated health workers poured their hearts into service, the centre's crumbling infrastructure and scarce medicines meant care often fell short of what the community deserved.

Atoruru's story mirrors Nigeria's painful healthcare paradox. In a world where maternal and child mortality casts a long shadow, 94% of maternal deaths and 95% of under-5 deaths occur in low- and middle-income countries like Nigeria; Atoruru faced a silent crisis. Globally, the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) seek to reduce the maternal mortality ratio (MMR) to below 70 per 100,000 live births and the under-5 mortality rate (U5MR) to below 25 per 1,000 by 2030. However, Sub-Saharan Africa, which accounts for more than two-thirds of maternal deaths, struggles with social inequality, deteriorating health infrastructure, and underequipped health workers. Nigeria is one of the countries most affected, with an MMR of 993 per 100,000 live births in 2023 and a U5MR of 110 per 1,000. The country's health system is experiencing strain because of socioeconomic challenges, limited access to skilled birth attendants (SBAs), and insufficient emergency obstetric care. With an MMR of 277 per 100,000 in 2020 and a U5MR of 19 per 1,000 in 2023–2024¹, Edo State is a shining example of improvement, but it faces challenges in remote areas like Atoruru, where access to healthcare was previously limited. The PHC, serving 16,263 people across farming communities, had become a place of last resort.

Before the Dawn: Striving Amidst Scarcity at Atoruru PHC

Nurse Aigbogun remembers those dark days: "We would record zero ANC visits some months because women knew we had no iron supplements or malaria prevention. They would rather stay home than waste a day's farming income on fruitless travel." Before October 2024, the PHC was a shadow of what a healthcare facility should be. The data tells a sobering story of those difficult months: from January to September 2024, the facility recorded between 0 and 7 ANC first visits monthly (with alarming lows of 0 in March and just 2 in September). Deliveries fluctuated between 0 and 4 per month, leaving many mothers, like 28-year-old farmer's wife Ivie Osaigbovo to take desperate measures. "I had my last baby at home with only my mother-in-law to help," she recalls, her voice trembling. "The clinic had no light, no water, and the midwife told us she had no gloves that day."

The immunisation records from those months reveal even deeper gaps in care. While some months saw 4-12 children fully immunised (May 2024 recorded 12), other months, like June, showed no data at all, a silence that speaks volumes about the erratic availability of vaccines. Nurse Ehiaghe Aigbogun, who has served at the PHC for about four years, remembers the frustration: "We would schedule immunisation days, only to turn mothers away because the vaccines never arrived. Watching children leave unprotected... it broke my heart every time."

The malaria prevention statistics paint an equally troubling picture. From January to September 2024, the records show no provision of Intermittent Preventive Treatment (IPT) for pregnant women or distribution of Long-Lasting Insecticidal Nets (LLINs), shocking gaps in a region where malaria remains a leading cause of mortality. Elder community leader Chief Osaro Idahosa shakes his head as he remembers, "We spend a lot of money rushing our children to other communities for treatment. The parents had gone to the PHC, but there were no malaria drugs that day."

The facility's struggles extended beyond clinical services. Stock-outs of essential medicines were frequent, with the data showing consistent stock-outs for key medications throughout 2024. Community engagement was nearly nonexistent; the records show zero outreach sessions in multiple months and only sporadic Ward Development Committee meetings.

The Turning Tide: ADHFP's Visionary Intervention

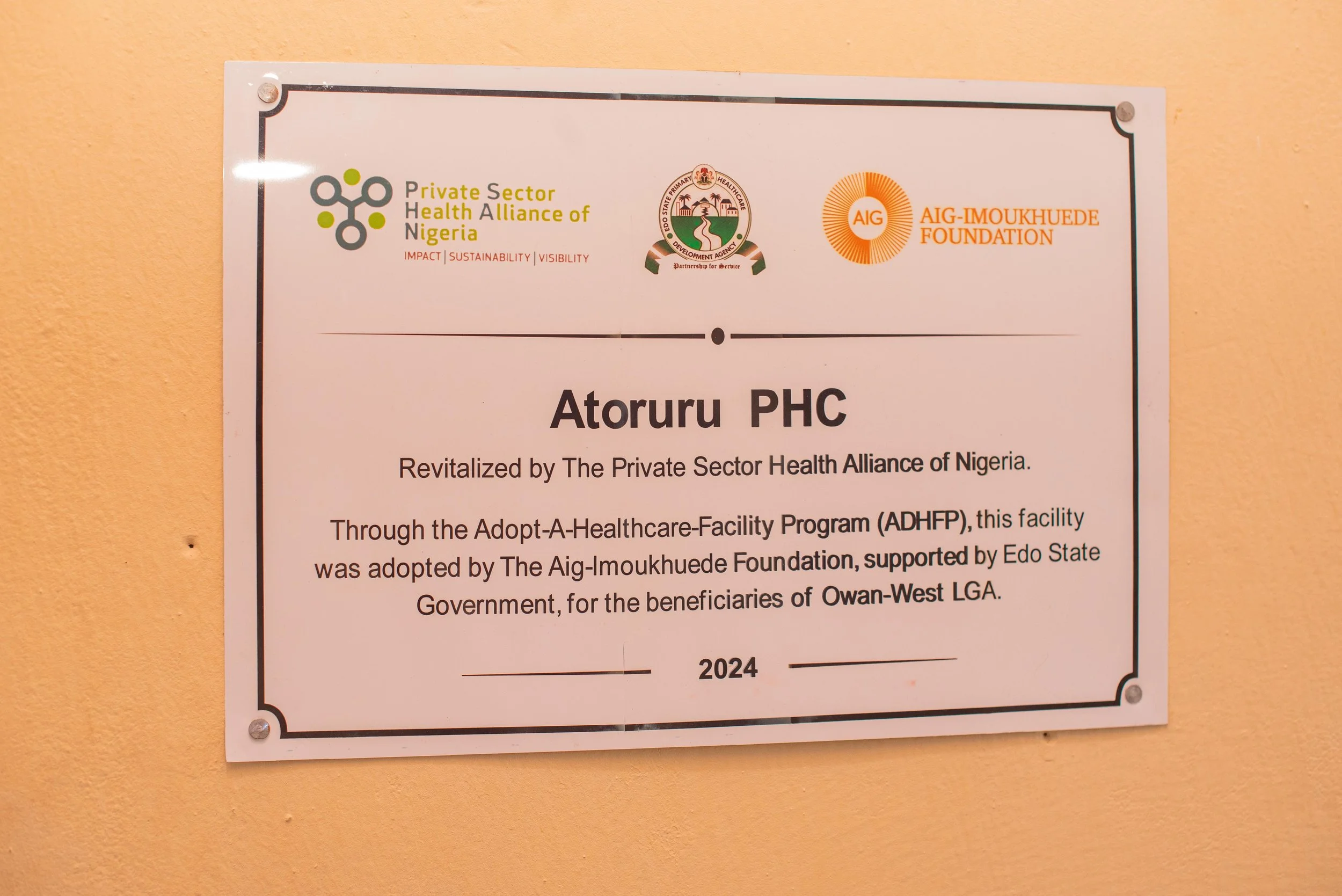

The turning point came like the first rains after a drought. When the Aig-Imoukhuede Foundation's intervention through the Adopt-a-Health Facility Programme (ADHFP) began in October 2024, the changes unfolded in ways both visible and profound. The facility was reborn: walls painted white, roofs sealed, and rooms equipped with delivery beds, a vaccine cold chain, and stocked shelves of antimalarials, haematinics, and LLINs. The freshly painted walls and new delivery beds were striking, but more transformative was the sudden reliability of services that communities had stopped expecting.

The immunisation programme's revival was immediate and dramatic. Where previously the facility might immunise 4-12 children monthly, November 2024 saw 38 children fully immunised, more than triple the previous peak. By February 2025, this number reached 48, with consistent monthly averages in the high 30s. "Now when we announce immunisation days, we prepare for crowds," laughs Nurse Aigbogun. "Mothers come from neighbouring villages because they've heard we never run out."

By December 2024, just two months into the revitalisation, the numbers began singing a new song. Maternal health services experienced an equally remarkable turnaround. ANC first visits, which had averaged just 3-4 monthly in early 2024, jumped to 9 in November 2024 and remained strong at 6-9 through May 2025. "At first I didn't believe the change," admits community midwife Ivie. "Then I saw our ANC register; pages that used to stay empty for weeks were filling up daily. Women were coming back for their second and third visits because we finally had what they needed." Deliveries at the facility increased from the previously 0-4 monthly to a consistent 4-6, with May 2025 recording 6 live births. Perhaps most significantly, the PHC began providing comprehensive malaria prevention for pregnant women; by May 2025, they had administered 32 IPT doses and distributed 47 LLINs to expectant mothers.

Perhaps nowhere was the transformation more lifesaving than in malaria care. Where once the records showed endless blanks under "IPT doses administered", by May 2025 the PHC had provided 32 preventive treatments to pregnant women and distributed 47 insecticide-treated nets. "Last rainy season, we almost lost three children from one compound," recalls elder Chief Idahosa. "This year, when little Adesuwa got a fever, they tested her immediately and gave the right medicine. She was playing the next day." Eghosa, a young mother in Atoruru left home early, her baby burning with fever in her arms, as she made her way to Atoruru Primary Health. This was her third visit this month, a stark contrast to a year ago when she wouldn't have bothered. "Before, we knew that going to the PHC was useless," she confesses, adjusting the baby on her back. "The nurses would just shake their heads and say, 'no drugs.'" Now when my child coughs, I come running because I know help is waiting."

Voices of Transformation

The data comes alive through the stories of Atoruru's residents. Young mother Blessing Osawe, cradling her healthy three-month-old, recounts her experience: "With my first child, I had just two ANC visits because the clinic was so unreliable. This time, I attended all eight sessions; they even gave me iron supplements and malaria prevention every month."

For 60-year-old farmer Pa Igbinovia, the changes hit closer to home. "Last year, we almost lost my grandson to fever. This year, when my granddaughter fell ill, the PHC had tests, medicines, everything. She's in school today because of that." The facility's staff share in this renewed hope. Community Health Extension Worker Grace Enahoro reflects on the difference: "Before, we recorded zero malaria tests some months because we had no kits. In March 2025 alone, we tested 48 children and 14 adults and treated every positive case immediately."

The true miracle, however, lies not just in the numbers but in how they have reshaped community attitudes. Health worker Osayande laughs, remembering the first outreach session after revitalisation: "We expected 20 people; over 80 came! Now when we announce immunisation days, mothers arrive before dawn." This renewed trust has created a virtuous cycle: more patients mean more accurate data, which ensures better supply planning, which brings even more patients.

A Model for the Future

As the sun sets over Atoruru, casting golden light on the PHC's newly painted walls, Nurse Aigbogun reflects on the journey while updating the monthly report. The numbers that once told a story of neglect now sing of renewal. For her, the real measure of success is walking through the door every day. "Yesterday, a woman brought her newborn just to show me," she smiles. "Not because the child was sick, but because she wanted me to see what our PHC helped her create. That's when I know that we have truly changed."

In a nation where too many health centres remain places of broken promises, Atoruru PHC stands as proof that with the right investment and community partnership, even the most neglected facilities can become beacons of hope. As Eghosa puts it while leaving with her now-healthy baby, "This was once a place where hope grew dim; now it is where our community finds new life." The Aig-Imoukhuede Foundation did not just renovate a building; they restored Atoruru's right to health, one life at a time.

References

WHO, UNICEF, UNFPA, World Bank Group, and UNDESA/Population Division. Trends in maternal mortality estimates 2000 to 2023. Geneva, World Health Organization, 2025

Federal Ministry of Health and Social Welfare of Nigeria (FMoHSW), National Population Commission (NPC) [Nigeria], and ICF. 2024. Nigeria Demographic and Health Survey 2023–24: Key Indicators Report. Abuja, Nigeria, and Rockville, Maryland, USA: NPC and ICF